Featured Posts

Historical Marker Day Trips Allow Familiar Locations to Yield Fresh Discoveries

By: Kirsten Hahn

Kirsten Hahn is a Radio-Television-Film and Journalism student at the University of Texas where she is a staff photographer for The Daily Texan.

This may not be the summer for elaborate, extended vacations. Expensive family outings to Washington D.C. or Mt. Rushmore might not make sense in the middle of a global pandemic. For example, you can’t drive to St. Louis or Chicago to see the Cardinals and the Cubs when their ballparks are closed to fans. So why not go on a more educational escape closer to home?

One day, one tank trips can be both safe and sensible and are a great way to become more familiar with the state where you live. No expensive maps or a guidebook is necessary. Just get out on the road, and look for historical markers, the bronze plaques you’ve probably zipped past all your life without stopping to actually read, or understand their significance.

Historical marker programs exist in all 50 states. The earliest markers were erected back in 1889 to commemorate significant people, places or events. They can be established by towns, universities, states, and they are literally all around us.

For example: there is a historical marker in Strasburg, Colorado, signifying the spot where the final link of the first coast to coast railroad in the United States was completed in 1870. There is another one in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, marking where the Wright brothers made the world’s first controlled, powered, and heavier-than-air flight in 1903. Or the historical marker in Hoboken, New Jersey, commemorating the first official baseball game played in the United States in 1846.

There’s one in Savannah, Georgia, marking the first steam ship to cross the ocean in 1819. Or the historical marker in Genoa, Nevada, commemorating the original Pony Express station in the state. And the historical marker in North Virginia Beach, Virginia, where the first permanent English settlers landed in 1607.

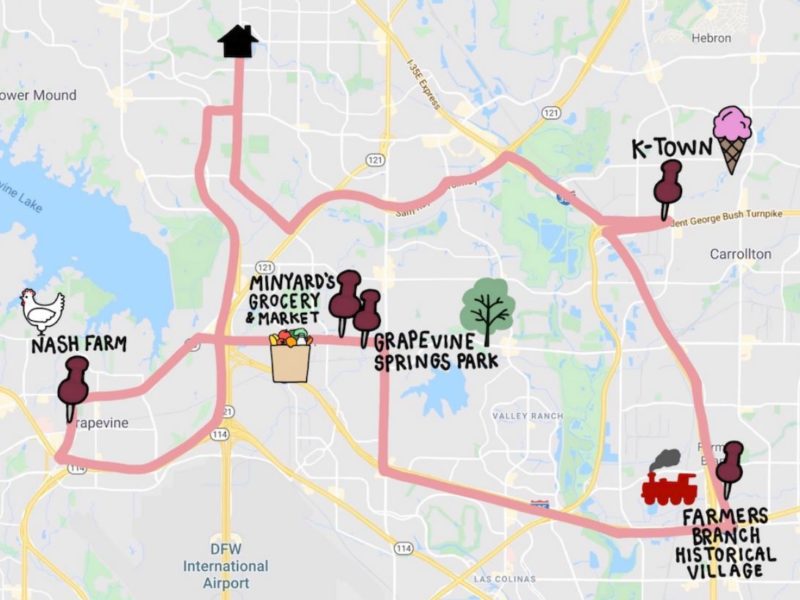

Route through North Texas history with historical markers leading the way

The states with the most historical markers are New York, Virginia, Pennsylvania, California, and Texas, but you should be able to find a number of them in your area with just a little bit of scouting. In Texas, where I live, there are over 3,829 markers.

When I was younger, my dad took me on a few road trips and made a habit of stopping at historical markers on the side of the highway. It always took us longer to arrive at our planned destination but getting there was truly most of the fun.

Historical markers don’t need to be a side stop on longer trips. You’ll find them wiithin a short radius of where you live. I easily located 100 markers near my house. On a recent trip, we started in Grapevine, a city just north of Dallas. The town was founded in 1844, a year before Texas joined the United States. It’s known for its wineries and also for its Christmas celebrations. It even got its name from a variety of wild mustang grapes that grew in the area.

Our first marker was Nash Farms. The farm is “one of the last remaining agrarian sites from the 19th century in North Texas.” In 1880, nearly all of the people living in this part of the state worked in rural areas. The restored farm gives modern Texans a view back into the beginnings of the state.

The original site was 450 acres and included a variety of crops and livestock. Nash Farms is not a working spread in the sense that it’s a commercial operation, but it’s a hands-on approximation of what life would have been like 150 years ago. The old farmhouse is open and completely furnished with 19th-century household appliances. A short walk brings you to cornfields and other plots being farmed. There’s even a store where you can buy homemade goods from people dressed in period clothes, many of whom made the items for sale.

There’s livestock all around the farm. A barn toward the back of the property has sheep and turkeys. The sheep weren’t very active on the day we visited but the turkeys pranced about as if they’d been choreographed. Chickens were everywhere and were too busy to entertain visitors.

Old Town Coppell on its farmers market day

Our second historical marker was in Coppell, Texas, and it was planted right in the middle of the historic old town built by the first settlers. Though surrounded by the sprawling Dallas-Ft. Worth metroplex, Old Town Coppell still feels like a quaint small town. A majority of the buildings have been restored yet look straight out of the 1800s. You can feel a strong sense of community. Houses are built around the town center so that you can grab a country supper or stroll down the beautiful streets without the constant sounds of city traffic.

The downtown marker identified a Minyard’s Grocery, an old wooden market originally in East Dallas that had been moved to Coppell and reassembled. The descendants of the pioneer family operated a chain of stores in the Dallas area until 2016. The store stands as a reminder of the importance of mom and pop businesses which contributed so much to the growth of the state. In towns like this, the grocery store essentially served as the community center. It’s where everyone gathered, not just to shop for the basic necessities but for conversation. And it’s still open for business today. (The Coppell Histgorical Society even offers tours)

Mom and pop Minyard’s store in Old Town Coppell still exudes the atmosphere, and the look, of early 20th Century Texas

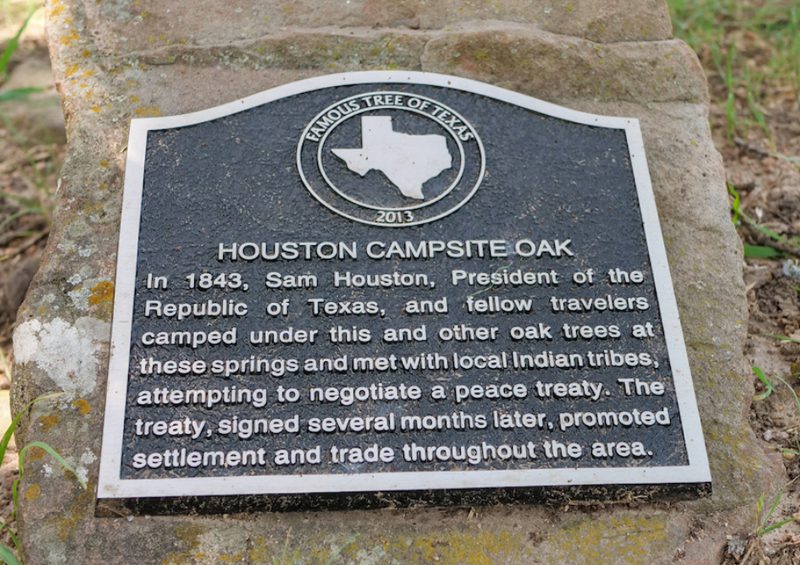

Down the road we found Grapevine Springs Park, where Sam Houston camped while negotiating the “Bird’s Fort Treaty” with local Native Americans in September 1843. The agreement covered the Delaware, Chickasaw, Waco, Tawakani, Keechi, Caddo, Anadahkah, Ionie, Biloxi, and Cherokee tribes and was meant to end hostilities between the tribes and white settlers. As with most treaties of that era, the agreement did not end well for the Native Americans, who eventually were moved off their ancestral lands and sent to Oklahoma. In an ironic development to the saga, the Supreme Court ruled this July that the formerly dispossessed tribes own close to half of the eastern part of the state. (Spoiler alert: They may need to change the historical marker!)

The park and its markers mainly focused on Sam Houston’s journey. Houston served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas. He also served in the United States Senate. The park also offers a little outdoor oasis in our suburban area. There are also small hiking trails, a recreation center and a local community garden.

A historical marker plaque under the oak tree Sam Houston slept under

Next stop: Farmers Branch Historical Park. Farmers Branch, Texas was named after the area’s rich farmland. And here. we were expecting one marker but came across more than expected. The park has 27 acres of historical homes and buildings. You can visit and go inside a cottage, church, general store, school, an old Texaco service station, a railroad depot complete with caboose.

The buildings here date back to the 1840’s, complete with 175 years of Farmers Branch history. At the front of the park is the Dodson House. This was the home of the first mayor of Farmers Branch in 1846. You can also see the Gilbert House, the oldest structure still on its original site in Dallas County. And then there’s the caboose, sitting beside the original depot. It dates to 1877 and was sold to the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad in 1881.

The vintage Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad caboose in Farmers Branch Historical Park and an old train from the same company

Our last stop was planned with lunch in mind. We headed over to Koreatown in Carrollton, Texas to learn about Korean Americans. This historical marker is in the middle of a shopping complex that offers a wide variety of Korean food and entertainment.

Korean immigration to Texas started in the early 20th century with immigrants mostly working at manual labor jobs. After that more Koreans came after the Korean War in the 1950s when U.S. servicemen married Korean women and relocated their families to bases like Fort Hood.

In 1965, the national origins quota system was eliminated thanks to Lyndon Johnson. It had limited foreign immigration visas to just 2% of the total number of people of each nationality in the United States as of the 1890 national census. New immigrants included nurses and other professionals who headed for metropolitan areas where they built flourishing communities. Its might surprise you to learn that Dallas has the highest Korean population in the state and fourth-largest Korean population in the U.S.

The Koreatown marker, as do many others in urban areas, captures contemporary history and lets us appreciate the often untold history in our own backyards.

Ssam Korean Grill in Koreatown, Carrollton

How To Plan Your Trip:

Although most states don’t have a complete map or data bank of all historical markers, there are resources to guide you.

https://www.hmdb.org/nearby.asp is a great resource to use for scouting out markers. It will pinpoint your location and display the nearest 100 markers. You can click on each one and look at photos to preview those locations. It has databases in all 50 states and works on cell phones and laptops.

From there you can put all of the locations into Google Maps. With Google Maps it will be easier to map multiple stops if you plan on visiting multiple historical markers.