Worldwide Pandemic Diaries

Worldwide Pandemic Diaries — Bangkok

As part of our continuing series of “Pandemic Diaries”, we publish situation reports from our colleagues and correspondents all over the world. In this latest diary, we hear from Dr. Will Yaryan, a former guest on our CBS radio show, Eye on Travel. He is an American expat blogger and English teacher, who filed this report from Thailand.

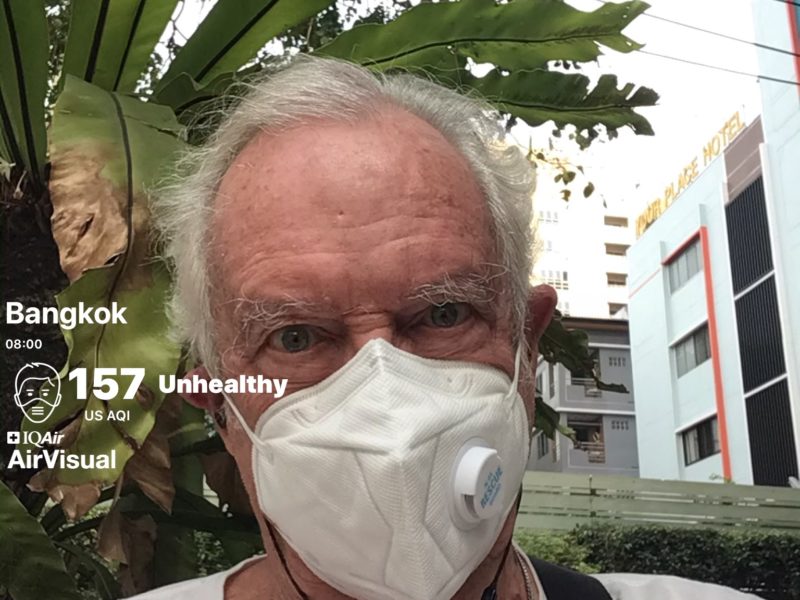

Bangkok residents are familiar with masks. The city suffers from periodic smog that grew so bad in 2018 that some people began tracking particulate levels with computer apps and wearing a N95 mask when it got severe. But these masks, which block the tiny dangerous PM2.5 particles soon sold out. Since the masks were uncomfortable and few Thais paid smog more than passing attention, it was mostly expats like myself and tourists that wore them.

I’ve been living for the last 12 years on the west side of the Chao Phaya River across from the Grand Palace in Pinklao which I like to describe as the Brooklyn of Bangkok. It’s an urban area with no particular charm and few tourists. My 9th floor condo has a magnificent view over the city to the southeast. The changing weather, along with the new elevated rapid transit train that began operation several months ago after years of construction, capture my attention each dawn.

In 2018 the smog lasted through January and February, two of the peak months for tourism. Last year it smudged the sky into April, and this year the pollurion only seems to be lifting now as the annual rains begin. As we shall see, the easy explanation that air pollution is the result of vehicles and factory pollution no longer holds weight these days. There is much less traffic now while people shelter in place, and the many factories are silent. The real cause can only be agricultural slash-and-burn practices which the government seems incapable of curbing. Just this week I saw smoke rising from a field in Ayutthaya north of Bangkok. Because of an additional forest fire, Chiang Mai in the north of Thailand was rated the most polluted city in the world for several weeks in March and April.

When the World Health Organization (WHO) made its announcement about a novel coronavirus in Wuhan on Jan. 12, I was teaching two sections of “Listening to English” on Mondays at the Buddhist university campus in Ayutthaya. The total of 80 students were mostly senior monks from Myanmar taking their final classes before graduating. My plan was to provide practice in listening by playing lots of English videos, in class and posting them in a Facebook group, about important global news stories. In a previous term, I learned students loved Greta Thundberg and were very interested in the climate crisis. So that was my primary topic. We began by discussing the disastrous fires in Australia, fears of war over Iran, and also the mass shootings both in Germany and in Khon Kaen in Thailand. Everything was going smoothly until the coronavirus began to take over in the final month of the class.

Just as I was trying to impress on my students the dangers of smog and the need for an N95 mask, the first cases and deaths in Thailand from the virus were announced. Chinese tourism had become crucial for Thailand’s economy and apparently thousands had come on tours in January from Wuhan. By the end of January there were 19 cases in Thailand, and all but a taxi driver were Chinese tourists. I began showing the students videos about Chinese and South Korean efforts to stop the virus. By the end of February there were 40 cases in Thailand and 60,000 in the world, and the virus had now been given the name COVID-19 by the WHO.

Our world turned upside down in March. From a small story on the list of global problems I asked my students to learn about to help improve their listening skills in English, the coronavirus quickly took over the world’s news headlines and video stories. On Mar. 11 the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic because of its rapid spread out of China and Asia to Italy, Spain and Iran. As March began, the first death from the virus in Thailand was announced. A cluster of over 100 cases were linked to a Muay Thai boxing match in Bangkok. Travel restrictions were rigidly imposed requiring 14-day quarantine for passengers from China, South Korea, Italy and Iran. The belief was that shutting down borders to all travel, wearing masks, maintaining social distance and washing hands frequently would curb the spread of the pandemic. I had no problem with that!

As I prepared my students for their final exam, more were willing to wear masks in class. It was no longer about smog but a deadly virus. I handed out free surgical masks my wife had gotten at her hotel. No cases had been reported yet in Myanmar but concern for their families was apparent. The Thai summer school vacation is traditionally held during the hot months of May and June and there was uncertainty among these senior students about graduation plans for June. Should they go home or stay at school in the dormitory?

My peaceful expat life in Pinklao was soon to change dramatically. First, while I was grading my students’ exams, the government cancelled Songkran, the traditional Thai New Year celebration in April which has grown into a major holiday involved elaborate water fights in tourist centers like Khao San Road. It’s also a time when workers in Bangkok return to their native province and villages to celebrate. Stay here, don’t go home, the government ordered. But then on Sunday, Mar. 22, it shut down the entire country, closing all businesses except for food and medical facilities. The not-unexpected result was a huge exodus with tens of thousands leaving Bangkok by buses for their homeland and refuge from impending poverty. Without jobs, rent could not be paid nor food purchased but at home there was always rice in this food-rich country. The fear of course was that the infected would spread COVID-19 throughout the country. That hasn’t yet happened.

As an old man now, my pleasures are few and simple. On days when I don’t teach English or prepare lessons, I like to swim in the condo pool in the morning and walk up to the mall in the afternoon for a hot cappuccino. After swimming or while drinking, I like to sit and relax by reading ebooks in my iPad. The shutdown ended that. Coffee shops closed or only took takeaway orders. Seats were removed. My temperature was taken before entering any 7-11 or Tesco Lotus and even in my condo’s lobby. The X’s on the floor told us where to stand for proper social distancing. No one could be seen without a mask. At my wife’s hotel, she was taught how to make washable masks in a workshop for staff. And she brought home boxes of alcohol spray cleaner. I could still walk but I could not sit, a stretch for someone who needs a cane.

At the end of March, the government declared a State of Emergency to consolidate control, and ordered a curfew from 10 pm to 4 am a week later. All international flights to Thailand were stopped, and only rescue flights could arrive or leave. On April 10 the government banned the sale of alcohol, something only done before on Buddhist holidays. Since I don’t drink much it was no problem but alcoholics all over Thailand began to experience true suffering. Because of less traveling and drunkenness, the usual enormous carnage on Thailand’s roads plummeted, perhaps saving more lives than COVID-19 claimed!

The good news in April for tourists and expats was a visa amnesty until July 31. The nation’s immigration offices had been clogged with huge crowds impossible to social distance despite everyone in masks. Thailand requires expats to report their address every 90 days and that requirement was suspended along with over-stay penalties for tourists unable to get flights home. Although residents were instructed not to travel within the country (my school is in another province), several airlines were allowed to begin limited domestic flights: Thai Air Asia, Thai Viet Jet, Bangkok Airways, Nok Air and Thai Lion Air. Some provinces made arriving passengers quarantine for 14 days.

Since no one seems sure what works and what doesn’t, Thailand is one of the luckier countries. Out of a population of 70 million and a work force of 39 million, there had been only 3000 cases reported and 55 deaths from COVID-19 by the first week in May. Other Southeast Asian countries have similarly low numbers with Vietnam the champ – so far no deaths. Does the heat make a difference (over 40 degrees these days in some locations)?

As a partly retired American expat living on a mostly secure Social Security income, quarantining in my condo has been a minor inconvenience. I have videos, books and social media. I’m Zooming and Skyping with a book club and creative writing group, and also with a group of friends in California. I’m teaching an English class on Zoom with a Thai professor in preparation for conducting online classes when school resumes in July. My wife, who worked in events planning at a Thai-owned boutique hotel, spends a day a week at her office but is thriving at home where she’s begun a garden on our balcony and cooks gourmet meals for me daily. We also order meals from our favorite restaurants which are quickly delivered by an army of motorbike drivers.

It would be nice to swim or to sit while drinking a cappuccino, but the lack of these comforts is nowhere near the severe problems faced by millions of Thais without jobs or income. The tourist industry which accounted for 20% of Thailand’s economy has disappeared over night. Factories crucial for exports have shut down with 700,000 out of work but eligible for unemployment (along with 11 million in the state’s Social Security system). The government promised to give 5,000 baht a month for 3 months to casual workers but changed its mind when the expected 3 million requests ballooned into 9 million. Many were unable to qualify and demonstrated outside government offices. It has been reported that there have been more deaths from suicide since the shutdown than from the virus.

Another group in distress are the country’s 17 million farmers who are suffering from a severe drought in some regions. My wife’s mother grows rice and corn in Phayao in the north and so far there has been enough rain. The considerable additional income farmers received from family members working in Bangkok has dried up and now that they have returned home there are more mouths to feed.

Despite photos and videos showing empty streets and sidewalks in central Bangkok, life in my neighborhood snapped back quickly after the March 22nd shutdown and the State of Emergency and curfew the following week. Thais rarely hug or touch anyway so social distancing was no problem. Just as I learned to take two showers a day after coming here because that’s what Thais expected, I now am a constant hand washer. Everyone wears a mask, even the beggar who has lived on a nearby bus bench for the last six months. Traffic is down a little, and long queues of taxis wait for the few passengers. But the sidewalks are crowded with the usual vendors selling food, flowers, clothes, and home-made washable face masks. On May 3 the government announced a soft opening which included parks and hair salons, and even the famed Chatuchak Market. And it cancelled plans for a continue ban on booze. Little changed in Pinklao. I’m still waiting for a seat and the pool remains closed. Now we’re being teased with the possibility of malls reopening on May 17 if new cases of COVID-19 and deaths from it remain low.

Now Thailand must decide how to move forward, how to balance health risks against the catastrophic damage to the economy caused by the shutdown. According to prominent commentator Thitinan Pongsudhirak in the English Bangkok Post on May 8: “The government of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha should now be listening to economists and social workers a little more than epidemiologists and medical doctors as Thailand’s virus-fighting priorities shift with twists and turns.”

With 4 million infected globally by COVID-19 and nearly 300,000 dead of the pandemic, less attention in Thailand, where the statistics are so small, has been paid to restarting the economy. No one here is protesting the wearing of masks and social distancing. Those protest activities elsewhere must seem quite strange to Thais. Perhaps the poor are more confident. They have survived for a long time without a safety net. Only time will tell which strategy, protecting health or rebuilding the economy, should be pursued more strongly.