Travel Tips

Day of the Dead Celebrations: Mexico’s Hungry Ghosts

While Halloween is a popular holiday in the United States, Mexico has long celebrated the Day of the Dead. Contributing writer Michelle da Silva Richmond, who has extensive firsthand knowledge of Mexico, explains the traditions and events surrounding the holiday.

Mexico, a country with roots deeply steeped in ancient indigenous and colonial Spanish cultures, celebrates El Día de los Muertos—The Day of the Dead, on November 1 and 2.

The ancient peoples of Mexico were obsessed with death, believing that it was necessary to die in order to be reborn. To guarantee this rebirth, they set aside two months in which to honor those who had gone before them.

The Aztecs set aside the ninth month of the Nahuatl calendar for the souls of deceased children; the tenth was to honor the adults. During this celebration, human sacrifices were made to insure the flow of fresh blood, so vital to regeneration.

Fiesta Time

Abundant offerings were laid beside the sacrificial stone, as young men donned in feathers and jewels gyrated to the beat of Nahuatl music. Although this was basically a solemn occasion, it was fiesta time in the Aztec world and a good excuse to drink pulque (a potent brew made from cactus).

Cemeteries throughout the country are decked out for the fiesta. (Photo courtesy of Riviera Maya CVB)

The Maya also believed that the spirits of the dead were allowed to visit their relatives between October 31 and November 2. October 31—dedicated to the children—is known as Palal Pixan. November 1 is dedicated to adults, while November 2 is for all souls—especially those who have no one to remember them—the lonely souls.

The evolution of the Aztec and Maya Empires were cut short by the Spanish conquest, and it was not difficult for the conquering priests to persuade the recent converts to shift their months of the dead to a two-day celebration, known as All Saints and All Souls Day. The resulting mesh of pagan and Catholic rituals formed an interesting tradition in Mexico which lingers to this day.

This link to the past is long and not always clear, but the celebration is a sacred tradition in Mexico. November 1 is set aside for the children who have died; November 2 is for adults.

A Spirited Celebration

On these two days, everyone feels morally obligated to go the cemetery to honor their dearly departed and convivir (spend time with them), and in true Mexican style, a social happening takes place.

Typical Mexican dishes are reverently prepared and toted—along with several bottles of the preferred drink—to the grave site. Tombs are decorated with the flower of the season, and pungent tzempazuchil (marigolds), candles, and incense are laid around the grave.

Once the stage has been set, the gathering begins around midnight with prayers, ending in the wee hours of the morning with drinking and raucous toasting to the “continued good health” of the deceased.

On the Yucatán Peninsula, the Maya tradition includes several rituals. One of the most important is the “altars” with typical food offerings: atole, tamales, mucbil chicken, pib, fruit, honey, seeds, and other treats. All are decorated with candles, flowers, and delicate branches. In remembrance of the children who have passed, they set out toys, candy, and cookies. The “pib”—the most important traditional dish—is a corn cake stuffed with meat and spices and cooked in an in-ground, hand-made oven.

Xcaret Park, on the Riviera Maya, will be hosting “Celebration of Life and Death Traditions” from October 30 through November 2, in honor of the holiday.

Though this rowdy practice has been banned in many cemeteries, it has become a tourist attraction in some parts of Mexico. In Mizquic, along the southern outskirts of Mexico City, or on Lake Patzcuaro’s island of Janitzio, in the state of Michoacán, worship of the dead draws tourists from all over.

In many towns, the homage takes place in the home, with altars decked out with flowers and photos of loved ones prominently displayed. On the November 1 feast of the children, a large table is set, laden with offerings of flowers, fruit, candied pumpkin water, toys, and candles. These gifts are left out all night so that the spirit may partake in the “essence” of the offering. The following morning, the “leftovers” are consumed by the family, with the belief that they have shared a meal with the missing family member.

A heartier meal is set out on November 2 in anticipation of the visit by the adult spirits, with additional treats, such as pan de muerto (a sweet doughy bread with crossbones emblazoned on its crust). Flowers, candles, incense, a bottle of tequila (if he enjoyed a nip), or a pack of cigarettes if he smoked (even if this was what killed him) are carefully set out for the unseen “guest.”

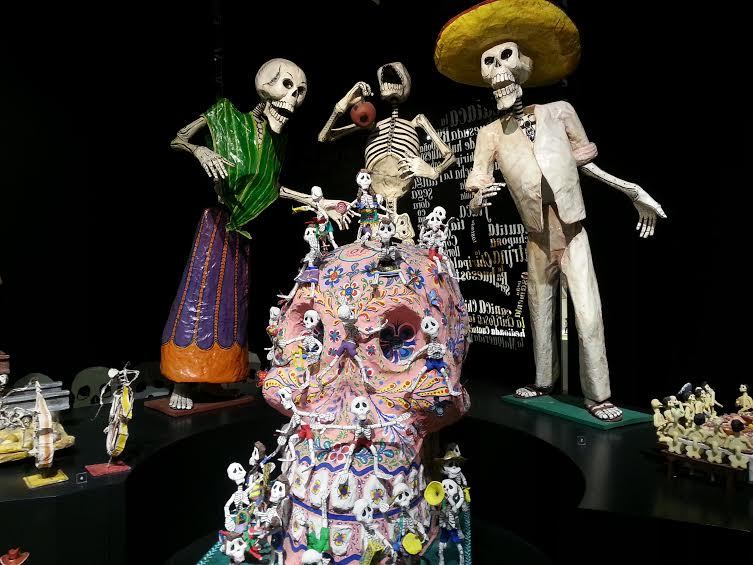

Highlighting the feast are small death figures made of marzipan, gruesomely fashioned for the ritual. Skulls with the names of the living etched on them, and skeletons decked out as brides, soccer players, musicians, and beggars complete the bizarre scene.

According to ancient tradition, eating these macabre confections is their way of laughing at death and proving that they do not fear it—a macho act of sorts. Another common way of celebrating—and the most palatable—is with calaveras or witty poems and epitaphs penned for relatives, friends, or celebrities who are still among the living. These written or drawn eulogies were made popular at the turn of the century by Jose Guadalupe Posada, a political satirist. Today, they are used mainly to poke fun at friends, or to mock the Grim Reaper.

Mexico’s fascination with death is legendary, and although the celebration is beyond the comprehension of most outsiders, it is a fascinating event to observe. Whether this is just another excuse for a fiesta, a way of discharging the soul, or merely a show of machismo, there can be no doubt that death takes a holiday in Mexico each November.

For more information about spooky events, visit:

- Ghost Tours & Black Dinners: 13 Halloween Hotel Events

- Tombstone Tourism: Historic & Humorous Cemeteries

- Zombie Runs & Events to Help You Prepare for the Apocalypse

- 15 Cities With Family-Friendly Halloween Activities

By Michelle da Silva Richmond for PeterGreenberg.com. Michelle da Silva Richmond is an award-winning travel editor and a member of the Society of American Travel Writers and the American Society of Journalists and Authors. Her articles have appeared in inflight magazines, consumer publications and newspapers throughout the U.S. and Mexico.